Sarah Jane WARREN (1856-1895)

Family Stories > 5th GENERATION > John Warren's Family

8. Sarah Jane Warren (1856 - 1895)

Spouse : John Christie (1848 - 1921)

Leonard Leslie Warren and Burdett LaunderGeorge Dixie Ford & Sarah Jane West

4th Generation

Charles James Warren and Elizabeth (Agnes) McNayRoberts Launder and Mary Burdett SalisburyJoseph Samuel Ford and Marianette KinghamArthur Cornelius West & Anne Eliza Devonshire

5th Generation

John Warren and Elizabeth Manning and Mary Manning

1. Elizabeth Warren & Richard Appleton2. George Warren3. Charlotte Warren & Francis Appleton4. Emma Warren & William Chase5. Oliver Warren & Elizabeth Hales6. Montefiore Warren7. Charles James Warren & Elizabeth (Agnes) McNay

8. Sarah Jane Warren & John Christie

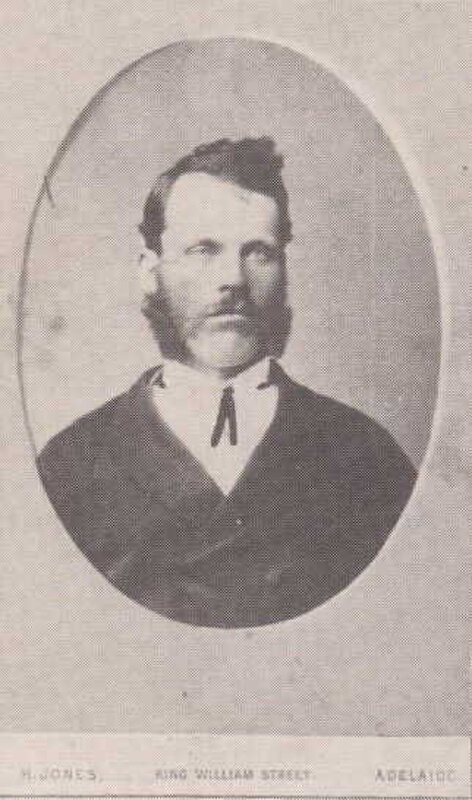

Sarah Warren John Christie

John Christie’s Parents – Alexander Christie and Ann Christie, nee Dowie

SARAH JANE WARREN Birth 1856, September 29 at Happy Valley, South Australia Marriage 1876, August 5 at the house of Richard Appleton, Happy Valley, SA Witnesses to Marriage Charles Warren, Grocer of Glenelg (Sarah’s brother) Alice Chase of Happy Valley (Sarah’s sister-in-law) Spouse John Christie Death 1895, January 11 at Edithburgh, Adelaide, SA Age at Death 39 years Cause of Death Graves’ Disease and Asthma Burial West Terrace Cemetery, Adelaide, SA Children 1 Rosa (Rose) Christie (1877-1963) 2 Ethel Jane Christie (1880-1899) 3 Charlotte Robenia Christie (1882-1962) 4 Beatrice Alice Christie (1884-1905) 5 Bertha Christie (1886-1879) 6 Violet May Christie (1889-1990) 7 Lendsley Harold Christie (1891-1940) |

JOHN CHRISTIE Birth 1848, March 25 at Rapid Bay, Yankalilla, SA Father Alexander Christie (1814-1883) Mother Ann Dowie (1820-1897) Siblings 1 William Christie (1841-1923) 2 Agnes Christie (1843-1927) 3 Ann Christie (1846-1905) 4 Maxwell Alexander Christie (1850-1926) 5 Margaret Christie (1852-1853) 6 Janet Christie (1854-1932) 7 Henry Samuel Christie (1856-1946) 8 Hugh Christie (1856- ) 9 Lambert Ferris Bowden Christie (1858-1934) 10 Hugh Watson Christie (1860-1927) 11 Jane Christie (1863-1898) 12 Jemima Christie (1865-1901) 13 Lillias Christie (1865-1952) Residences Rapid Bay, Yankalilla, SA Hog Bay, Kangaroo Island, SA Edithburgh, Daly, SA North Brighton, SA Occupations Mail courier, General Store Owner Death 1921, February 13 at ‘Home for Incurables’ in South Australia Age at Death 73 years Burial West Terrace Cemetery, Adelaide, SA |

Sarah Jane Warren & John Christie – Their Story

1848 – Birth – John Christie

John Christie was born in 1848 at Rapid Bay, Yankalilla in South Australia. Nestled between a long sandy beach and towering cliffs, Rapid Bay is 105 kilometres south of Adelaide and is reached by a steeply descending road from the main Normanville-Cape Jervis Road. Rapid Bay is where Colonel Light first stepped ashore to form the new colony. He named the bay after his ship the HMS Rapid. He recorded the event by engraving his initials and date on a boulder, now incorporated into a beachside monument. It is reported that he said “I have hardly seen a place I like better.”

John Christie, parents were Alexander Christie and Anne Dowie, was one of thirteen children.

1856 – Birth – Sarah Jane Warren

Sarah Jane Warren was the eighth and last child born to John Warren and Mary Manning in Happy Valley in South Australia.

1871 – Mail Tender – John Christie

At the age of 23 years in 1871, John successfully tendered for the delivery of mails for the areas of Talisker, Hog Bay and Kingscote and with the help of his father, transported the mails across the Backstairs Passage for many years.

GENERAL NEWSThe following tenders for the conveyance of inland mails for three years, commencing 1st April, have been accepted –Swannel & Wallace – Milang and Meningie - £620/-/-d.John Christie – Talisker, Hog Bay, and Kingscote - - £84/-/-d.1871, March 18 – Newspaper Article from Southern Argus (Port Eliot)

1876 – Marriage – Sarah Jane Warren

In 1876, John Christie found time to discover Sarah Jane Warren and they married in the home of Richard Appleton in Happy Valley, Richard being the husband of Sarah’s older sister, Elizabeth Warren.

1876 – Constable for Cape Jervis – John Christie

It was also in 1876 that John was appointed as a constable for Cape Jervis.

RAPID BAYThe following constables were appointed – Second Valley Ward, William Hoswell; Bullaparinga Ward, Thomas Lord; Cape Jervis Ward, John Christie1876, August 29 – Newspaper Article in South Australian Register

1877-1880 – Children Born

In 1877, John and Sarah’s first child was born and they named their baby Rosa Christie. A second daughter followed in 1880 named Ethel Jane Christie, both being born in Delamere, Yankalilla.

1880 – Relocation to Hog Bay

John continued to deliver the mails for many years, but in about 1880 when he failed to have his mail delivery tender renewed, he chose to move to Hog Bay where he set up a general store which was referred to as “Christie’s Store” and was located near the Church of England.

He sold a variety of goods from potatoes at one penny per pound to calico (a material) at six pence per yard.

1882 – Another Daughter

It was at Hog Bay on Kangaroo Island, that John and Sarah’s third daughter, Charlotte Robenia Christie was born in 1882.

John clearly had a passion for Kangaroo Island and was not afraid to publicly condemn what he saw as a poor return for public moneys spent on shoddy workmanship.

TO CORRESPONDENTS“John Christie”, Hog Bay, writes –I was rather surprised on taking a trip to Cape Jervis about ten days ago at the very small improvement made to the boat harbour for the £100 spent there, and more so when I read in the Marine Board report that £175 had been spent.But what for I am at a loss to find out, as the whole amount done could have been done for £50.Besides, it is mentioned in the Marine Board report that there is now from two to three feet of water there at low water – a statement altogether untrue, as my boat was aground for two tides in the deepest part in the centre of the harbour, notwithstanding she only draws eighteen inches of water when ballasted. There was but eight inches of water in the harbour at the time.1883, May 24 – Newspaper Article in South Australian Advertiser

John was also not backward in challenging what he considered to be erroneous or maligning information as some of the newspaper articles demonstrate –

TO CORRESPONDENTS“Able Seaman” writes –Mr. John Christie, in his letter re the Cape Jervis boat harbour, states that he has often seen less than eight inches of water in the harbour, adding in support of his assertion the number of years he has resided there, and offering to bring witnesses to prove his statement.Now I deny this, unless Mr. Christie intended to convey the idea that this shallow water existed on the bar, which at low tide is almost dry. This bar banks up the water and thus forms the harbour, which in many places is not less than one foot deep at low tide.He complains of the work performed by the Marine Board. I wish to state that they have caused to be moved several large rocks and a portion of the bar, by which means the entrance is, and the harbour generally, are much improved.We can publish no more on this subject.1883, July 28, Newspaper Article in South Australian Weekly Chronicle

The editor of the newspaper clearly thought the subject should be closed, but not before John had one more word to publish –

TO CORRESPONDENTS“John Christie” writes in answer to “Able Seaman” respecting the deepening of the boat harbour at Cape Jervis.Mr. Christie says the statement of “Able Seaman” that he never knew the water in the harbour to be as shallow as eight inches, displays his ignorance on the subject.Our correspondent has been acquainted with the harbour for 27 years, of which time he has lived 23 years within a distance of 300 or 400 yards from the harbour, and is able to asset positively that he has often seen it when there has been less than eight inches of water.Plenty of witnesses, he says, can be brought forward to prove this statement.Mr. Christie is still of opinion that very little has been done for the money spent on the harbour, in fact, the expenditure has been altogether wasteful.1881, July – Newspaper Article in South Australian Weekly Chronicle

1882 – Property Ownership

According to “Kangaroo Island Past and Present” complied and published by Kingscote, CWA, as at April 1 in 1882, John Christie of Hog Bay, farmer, occupied one rood (this equals about ¼ of an acre – an average house block) located in the township of Penneshaw and another 100 rood (equal to 25 acres) in Dudley, Carnarvon for which he paid £2/15/-d.

A month later by May 4 in 1882, he is listed as a storekeeper of Hog Bay and occupied 2 roods (1/2 an acre) in the township of Penneshaw for which he paid £28/10/-d.

1883 – Kangaroo Island

In 1883, a newspaper reporter travelled to Kangaroo Island for a few days to report on what he saw. His report is rather lengthy, but sufficiently interesting to quote in full – and of course, John had to make his reply.

A FEW DAYS IN KANGAROO ISLANDMore than eighty years have elapsed since the anchor of the Investigator was dropped in the calm waters of Nepean Bay, and her commander, the intrepid Flinders, gave the name of Kangaroo Island to his new discovery.It was no misnomer then, but though no great progress has been made in settlement since that time, those who visit the island now are tempted to believe that it was christened on the lucus a non lucendo principle. Settlers of twenty years standing may be met with who have never seen kangaroos on the island and are even sceptical about their existence. The favourable account which Flinders gave of his discovery brought Kangaroo Island into temporary notoriety, and his glowing description of the wealth of bird life on the American River, inspired James Montgomery with the idea of his poem, “The Pelican Island”.It was not, however, till 1836 that any attempt at settlement was made, but in that year, the Cygnet and the Rapid landed the first pioneers of South Australia at Kingscote Point, in Nepean Bay.It is easy to understand that the settlers did mot regard the dense scrubs which covered the island with a cheerful eye, and the early removal of the infant colony to the mainland is not astonishing. Henceforward, Kangaroo Island, though not entirely deserted, bore a bad reputation and little or no endeavour was made to test its capabilities and resources. A few settlers, however, lingered on its northern shore, and some small whaling stations were established on its southern coasts.Years rolled on, and the islanders pastured their small flocks and grew little patches of grain in undisturbed quietude. The tide of settlement had passed by the island and showed no signs of a reflux. Telegraphic communication with the mainland was established, and the electric wire traversed the island from Cape Willoughby on the east to Cape Borda on the west. The busy stream of intercolonial traffic poured through the Backstairs Passage and passed the neglected island unheeded, but at length the progress of agricultural settlement, checked for a time by the droughts of the Northern Areas, is being turned southward, the scrub lands of Kangaroo Island are being cleared by the axe of the selector and the work of settlement has commenced in earnest.The Hundred of Menzies, which comprises the country for six or seven miles west of the Bay of Shoals and Nepean Bay, has been surveyed, and the greater part of it selected. Hundred of Dudley, as the eastern peninsula is called, has also been surveyed and a great portion of it taken up. Between these two, but lying more to the southward, is the Hundred of Haines where three survey parties are now at work. Parties of intending selectors are crossing over to the island every week and carefully exploring the country. Several stores have been opened and two small townships have been laid out – and the allotments sold at good prices – on the shores of Nepean Bay. With a most salubrious climate, a certain rainfall and a soil which, though not of uniform excellence, has produced good crops where it has been tried and which has satisfied the critical judgement of a host of practical selectors, there seems to be no reason to doubt that agricultural settlement on Kangaroo Island will be both successful and extensive.There are several ways by which the passage between the mainland and Kangaroo Island may be accomplished. Once a week a little sailing boat leaves Yankalilla with the mails for Hog Bay and Kingscote, but as the date of sailing depends upon the state of the weather and as she is not unfrequently two or three days behind time, no one who has not a great deal of superfluous leisure cares to patronize that route.Several ketches ply with more or less irregularity between Port Adelaide and Kingscote, but unless they are so fortunate as to obtain favourable winds, the trip may take four or five days. When this happens, even the comforts, luxuries and conveniences of a ketch pass upon the passenger, and not even the distraction afforded by intermittent attacks of seasickness, can prevent the voyage from becoming monotonous.The third and best way of getting to the island is by means of the South Australian Fishing Company’s steamer, the Dolphin, which is now making three trips a week to Kingscote, and in fair weather accomplished the passage in seven or eight hours.Starting from Glenelg jetty at midday, a pleasant run down the Gulf brings us to the entrance of Nepean Bay a little after dusk. A low bushy island about two miles off Kingscote Point, continued by a long sandspit which is partly under and partly above water, protects the entrance to the bay so effectually as to render it almost land locked.Rounding the sandspit, under the skilful pilotage of her smart and obliging skipper, the Dolphin ranges alongside an ungainly hulk moored about half a mile from the little Kingscote jetty. The hulk, Byron, is the property of the South Australian Fishing Company and serves as a coal magazine as well as a fishing depot. The story goes that the Byron was built to explore the polar regions in search of Sir John Franklin, and she is certainly heavy and clumsy enough to stand a good deal of knocking about among ice floes. She is quite deserted, for the man in charge is away in his boat on a fishing excursion, and some little delay occurs before a sailor manages to scramble on board and make the Dolphin fast to the hulk.Kingscote boasts no house of accommodation, and the passengers spend the night on board in comfort – in the morning they must shift for themselves. Daylight shows the outline of the coast, and under a bright sun and clear sky the prospect is by no means unpleasing. The nearest shore rises to the westward in a bold bluff above which bright green slopes of grass and crop sweep upward to a hill, on which stand three houses in a row – the homestead of the oldest Kingscote settler. The open space is not, however, very extensive, and thick scrub prevails nearly all around. To the northward the bluff sinks gradually to a low sandy point, beyond which stretches the deep indentation of the Bay of Shoals. Here rise the ruins of a house or two – relics of the first settlement.Following the coastline for about a mile to the southward we come to Beare’s Point, on which the Telegraph Station stands, and near which the cable which connects Kangaroo Island with the mainland enters the sea. A large white pyramidal beacon indicates the locality of the submarine wire and warns incoming craft to keep at a safe distance. Beyond Beare’s Point the coastline trends south-westerly and thus, with the Bay of Shoals on the north, and Nepean Bay on the south, the Kingscote Peninsula is encircled on three sides by the sea. On the southward side of the Telegraph Station the private township of Queenscliffe is laid out in allotments, which have sold well. The town itself remains to be built, but the Kingscotians have no doubts as to its future. It is intended to be the summer watering-place of Adelaide and is expected to become as favourable a place of fashionable resort as its Victorian namesake. But it has a rival. Two miles down the bay is the Government township of Brownlow, on comparatively low, but dry and scrubby ground, The white pegs of the surveyors glisten here and there among the mallee, a galvanized iron store rears its roof above the low scrub and a shoemaker’s shop is in course of erection. A written notice attached to a sturdy sapling informs all whom it may concern that an application has been made for a publican’s licence, including a billiard-table licence, on December 12, 1882, at the corner of Hurd and High streets. This corner is indicated by a peg, but that is the only indication which at present exists of the Brownlow Hotel.The flat, uninteresting looking beach, is piled thick with common shells of few varieties at high-water mark. The bay is here very shallow, but it is a favourite spot for receiving and discharging cargo. The boats of the ketches are beached and loaded at low water and are floated off by the tide, and in delivering freight the operation is reversed. It is agreed on all hands by the islands that they must have a jetty, but they are by no means agreed upon the best site for it. The Brownlowites maintain that it would be absurd to put the jetty at Queenscliffe on a peninsula which is two miles out of the way of the general traffic of the hundred. They also urge that Queenscliffe is a private and not a Government township and that it would cost as much to erect the jetty there as at Brownlow. The Queenscliffites, on the other hand, laugh at the idea of constructing a jetty a mile long at Brownlow while at their own site the work can be done at one fourth of the trouble and expense. Between the opposing parties the Government may find a very fair excuse for postponing the consideration of the jetty question to the indefinite future.Pulling in from the Dolphin to the narrow little jetties at Kingscote we pass several ketches loaded with road metal from the bluff. One of them has apparently taken in rather too much of this useful ballast, for she is aground, but that is of little consequence for she will float off at high water.Right under the bluff are two little nondescript buildings for the convenience of the men who loosen the readymade road metal, of which the bluff is mainly composed, and send it rattling down a steep shoot into little trucks, which, when filled are run along the jetty rails and discharged into the boats of the ketches. With all this material for road making close at hand it seems strange that no attempt to form anything like a road has been made on the island.The first impression which Kangaroo Island makes on the stranger at this time of the year is one of all-pervading sloppiness. Everything is streaming with moisture, pools of water lie in every little depression, even gently sloping pastureland is boggy and little streams pour over the bluffs or gash out at their bases. The average rainfall is said to be about twenty inches, but this must be greatly exceeded during the present year., During the month of May no less than eight inches fell, and as it had at the time of the writer’s visit at the end of June, rained every day during the month, the rainfall for June is not likely to be much less.Clambering up the bluff at its most accessible (and muddy) spot, we find ourselves on a fine agricultural section, belonging to the South Australian Company. It is under lease for five years to Mr. De Coque, who is busily engaged in preparing to put in his crop and in clearing scrubby portions of his holding. Two or three parties of intending selectors are met with, coming back from their explorations. Their report is not encouraging to some of our passengers bound on a similar errand who have avowed their intention of walking round to Hog Bay, in Dudley Island. It appears that all the land near the coast, and indeed the greater part of the hundred, has been taken and that to reach and examine the unappropriated blocks requires considerable fortitude, perseverance and disregard of hardships. Tomahawks, provisions, camping utensils and rugs must be taken – a great deal of wading through mud and water must be done, wet and cheerless bivouacs with the ceaseless serenades and still less agreeable personal attentions of myriads of mosquitoes mut be endured. Our passengers straggle off into the scrub and follow the inland telegraph line for a couple of miles and then return to the steamer and go back to Adelaide, quite satisfied that land-hunting on Kangaroo Island just now is not a holiday pastime.Some of the returning selectors, however, are men of a different stamp to this. They made up their minds when they came to the island as to what they meant to do, and they have done it. They do not effervesce in praise of the country they have seen, but on the whole are very well satisfied. One of them has left his overcoat behind, but it does not matter, as he remarks that he will be back again next month.One of the peculiarities of the island is that there is hardly any grass on it. Wherever the scrub grows, and that is everywhere, unless a clearance has been made with the axe – it kills all other vegetation. But when once the sunlight finds its way unobstructed to the soil the herbage springs up and grows luxuriantly.At the back of the telegraph station a little cleared paddock is covered with a thick growth of succulent herbage, which a couple of horses do their best to keep down. The stationmaster himself seems to enjoy his comparatively lonely life heartily, and though he has been seven years in the same spot has no wish to leave the island. Isolation and quietude have not affected his spirits, and he laughs and talks over the little incidents of the station with unaffected glee and contagious hilarity. Newcomers to the island, he says, sometimes rush up to the office in great haste and say, “I want to telegraph money to Adelaide.” To which he replies, sorry to say, you can’t do it. “Can’t? Why not? Ain’t this a money order office?” A crushing negative is the response and the disappointed one ejaculates, “Well, I’m blanked! Will you give me some stamps then?” Whereupon he is taken confidentially to one side, a low sandy point about a mile to the northward is indicated, and then he is told that he will find the Post Office there. The course of the disconcerted seeker after postal conveniences may be traced long after he has disappeared from sight by the expletives with which he condemns the Government in general and the Postal Department in particular.The Kingscote post office is an institution of undoubted antiquity and as such is entitled to the veneration and respect of the ancient order of islanders, but it is ingeniously situated so as to be as much out of the way as possible.The newcomers, however, do not look at the matter in a proper light and are agitating for reforms and innovations with regard to postal and other matters which the ancient inhabitants have never dreamt of.The ruins of a jetty stretch out into the sea from the Post Office point and behind the thick scrub, which there grows close to the water’s edge, is a well of pure fresh water sunk keep in the loose sand, and timber-lined to prevent it from collapsing. The heights at which the water stands in the well appears to be below sea-level, but it has no taint of brackishness. Indeed, all along the beach it is said that fresh water can be obtained by digging a foot deep in the sand above high-water mark.On the slope of the hill behind the Post Office and some 200 yards distant is a little cemetery. It is unenclosed but a few graves are protected by iron railings and marked by simple headstones on which are engraved the names of the dead who died for the most part a quarter of a century ago.Kingscote does not possess a place of public worship but occasionally a Church of England clergy man comes over from Yankalilla and holds service in a private house. The Wesleyan Conference has lately sent a bush missionary to Hog Bay and he also visits the settlement at intervals. A provisional school was at one time held in Kingscote, but the grant has now been removed to Hog Bay.There is not a policeman on the island, though there are several Magistrates. It does not appear that either of these gentlemen is called upon to exercise his magisterial functions very often. The islanders are a peaceful race and where there are no public houses there is seldom any breach of Her Majesty’s peace.The older settlers, though the ploughing has been delayed by wet weather, have nearly all got their seed in, and towards the Bay of Shoals and on the Cygnet River there are some very promising looking crops. The newcomers, however, are for the most part hard at work fencing, clearing, and ploughing, and making strenuous endeavours to put a certain quantity of land under crop this season. The general method of clearing is by the axe, the ‘stump-jumper’ rendering the process of grubbing not absolutely necessary. Near the Salt Lagoon, about six miles from Kingscote, and westward from the Bay of Shoals, an enterprising selector has imported a scrub-roller, for, though it clears the land at leas expense than hand labour, the work is not so clean and the machine cannot be used in all sorts of scrub,. Where the growth is slight and elastic the bushes spring up after the roller has passed over them and in very strong and stiff scrub it cannot be worked at all. The cost of clearing the land with the axe is said to range from 7 shillings to 18 shillings an acre, according to the density and character of the scrub.The soil itself so far as can be judged from a few days’ inspection, is somewhat patchy, alternating from a light brownish clay on the little elevations to a rich black soil on the more level lands, with here and there patches of what appears to be very nearly pure white sand, nevertheless, some of this latter country has been put under cultivation in confident expectation of a good return. Wheat and barley are the cereals which are most generally grown – the latter having a high reputation among the Adelaide brewers. Some excellent samples of wheat were to be seen which it was said had been grown on land that had been under crop for over ten years and have never yielded less than fifteen bushels to the acre. Phenomenal yields of fifty and sixty bushels to the acre are spoken of, and few of the farms will own to a less average than fifteen bushels, while twenty bushels is the general estimate.Nevertheless, the official returns give eleven bushels as the average for the island, and this is by no means despicable. Root crops are said to thrive well and give good returns, and as the proof of the pudding is in the eating, some excellent potatoes, when subjected to the test of the palate, may be taken as good evidence that the statement is not without foundation.About two miles from the embryo township of Brownlow, the Cygnet River, after a long and tortuous easterly course, empties itself into Nepean Bay. The mouth of the river is plainly indicated at some distance by a low sandbank, which lies two or three hundred yards from the beach and presents an effectual bar to inland navigation. It is not, however, beyond the bounds of possibility that the channel may be ultimately cleared, so as to allow barges to ascend the river. A great many selections have been taken up on its banks and water carriage for grain and goods to and from the coast would be a substantial boon to the settlers. For some distance from its mouth the bank of the Cygnet are mere salt marshes, but higher up the land, though at first cold, hungry and now little better than a swamp, has been taken and securely fenced, and a few miserable looking sheep are pasturing upon it.A Government bridge crossed the Cygnet some three miles from the sea, where the telegraph track leads to American River. Here the river is over its banks, and when its waters are dammed back by the flood tide, the surrounding country presents the appearance of a half-drained lake. A little way below the bridge on the south bank of the river is a Government reserve for recreation purposes. The islanders utilize it as a racecourse on which they hold their mid-summer saturnalia – the solitary dissipation of the year.Crossing the bridge and following up the river for a few miles we pass over a considerable quantity of ploughed land in a very moist condition, succeeded by flourishing green crops, which, however, look as if they had received quite as much rain as was good for them. A number of farms in this locality show signs of having been settled for some time.As the ground rises timber is met with – red genuine gum trees, sixty and seventy feet high, growing straight and strong and lusty. This is a rarity, for except on the back-country ranges the timber of Kangaroo Island is represented solely by scrub which seldom reaches the height of twenty feet. Just below the timbered country Mr Daw, farmer, storekeeper and Magistrate has resided for over twenty years He takes a more lively interest in the progress of the island than some of the earlier settlers, and at the time of the writer’s visit had just sent notices round the district calling a public meeting (the first ever held on the island it is said) to decide upon the best site for a jetty on Kangaroo Island. With him resides for the present Dr. Shaw, the Health Officer of the island, who is a settler of only a few weeks’ standing. It was certainly high time that medical aid was brought with reach of the inhabitants, for though the climate is wonderfully healthy, such accidents as broken bones do occur sometimes, and the transport of the patient to Adelaide was no trifle.From the Cygnet bridge to Kingscote the track, for road it cannot be called, is in a semi-liquid state, and without wading it is impassable to the pedestrian for some distance. Even on the rising group it is in many places a quagmire in which a loaded dray would sink to the axles. In the scrub through which the track passes the ‘wurlies’ put up by land-hunters to give them a night’s shelter from the weather are occasionally seen. Here and there the hut of a settler who is hard at work clearing his land may be met with. These temporary homes are very simply and quickly manufactured. Two forked upright stakes are driven into the group and a sapling is laid in the forks to serve for a ridge-pole. Against this, sheets of corrugated iron are placed in a slanting direction and the house is built. The shelter is rude, but tolerably good, and the selector has to put all his time and energies into the task of preparing his land for the plough and if possible getting crop from it in his first season.Two miles from Kingscote on this telegraph track a blacksmith has taken up land and proposes to ply his trade as soon as he can get a little settled.It is by no means easy to obtain stores or implements from the mainland. The ketches have hitherto had a monopoly of the freightage and their arrivals and departures are very irregular. In some instances, people on the island have been waiting more than a month for goods, which should at the latest have been delivered with a week. Now, however, that the South Australian Fishing Company’s steamer is running regularly and frequently between Kingscote and the port, there should be no difficulty in securing the prompt shipment and delivery of goods.So far as fishing is concerned the steamer does not appear to be particularly useful, and the local boats have not had much success in their efforts to provide her with the finny cargo which the Directors of the Company fondly expect. The great quantity of fresh and muddy water which has been poured into the sea from the island during the past two months has naturally had the effect of driving the fish away from the coasts, and consequently the line and the net are often used in vain.Politics can scarcely be said to be dead in Kangaroo Island, since they have never been born. The island forms part of the electorate of Encounter Bay, and there are two polling places, one at Kingscote and the other at Hog Bay. It is not on record, however, that any representative of the electorate has ever considered it his duty to visit and enquire into the wants of the islanders. The population three years ago was estimated at 400 and since then selectors have been and are steadily pouring in. When the next general elections occur, it will be most likely be found that the Kangaroo Island votes will be of some importance.The new settlers are generally energetic and pushing men, who, have been accustomed to take an interest in the affairs of the colony and who will not be content to suffer neglect passively. They have already begun to agitate and to press for consideration in several matters which concern their interest closely. The island has many wants, some of which must be supplied by private enterprise, while others should be met by the Government. In the first place a jetty is wanted for the convenient discharge and receipt of cargo. On the best site for the jetty, as before stated, great difference of opinion exists among the settlers and legitimate considerations are subordinated to local jealousies. The Brownlow party is evidently the stronger of the two, numerically considered, but the Marine Board in deciding on the merits of the case by actual investigation will not probably be greatly influenced by a divided local vote.With regard to postal affairs, there is no room for any difference of opinion. There can be no sufficient reason why the Post Office and the Telegraph Station should be in different hands. The latter is a necessity, and the former could be incorporated with it, and a Money Order Office and a branch Savings Bank opened in addition at a very small expense, and to the great convenience of the islanders. The means of postal communication with the mainland are at present ridiculously insufficient. The mail comes from Yankalilla in a small sailing boat once a week. It is due at Hog Bay and at Kingscote every Saturday, but in rough weather – and the Backstairs Passage is frequently very rough – the mail is delayed till Tuesday or even Wednesday. The islanders have, no doubt, only their own inaction to blame for the continuance of this arrangement, but now that a steamer regularly makes the trip from Adelaide several times a week, there should be no delay in bringing the necessity of improved postal communication immediately and prominently before the Government.A school is another of the wants of Kingscote, for though there are not a great many children in the neighbourhood at present, there are enough to make a good beginning, and when the selectors bring over their families, the absence of any means of acquiring the rudiments of an education will be severely felt.The want of some house of accommodation is another drawback to the settlement, and it is strange that no one has gone in for so profitable an undertaking. The township of Queenscliffe may perhaps become a favourite watering place in time, but that time will be indefinitely postponed unless some sort of accommodation is provided for visitors. At present when a man steps ashore at Kingscote, he must either take up his quarters in the scrub or submit to the humiliation of begging a night’s lodging from some settler. There is not a flour mill in the island and considering the quantity of ground in cultivation and now about to be put under crop, it is rather strange that no one has thought it worthwhile to undertake what appears to be a very promising enterprise.It would of course be absurd for anyone to give an authoritative and decisive opinion on the prospects and capabilities of an extensive island, after a few days spent under decidedly unfavourable circumstances, in cursorily exploring a small portion of it. The general impression, however, produced by the visit is that Kangaroo Island has been too long neglected and that though much of its surface may be unfit for agriculture, it will be found that this is still ample room for profitable settlement and cultivation. As yet only a very small part of the island has been surveyed and the rest of the surveyed lands have been already taken up, but there is little reason to doubt that when the surveys are completed other portions of the island will be found of as good quality as the lands already selected. A series of ranges runs through the island from east to west and on the northern side on the ‘backbone’ as it is called, the telegraph line goes to Cape Borda, about ninety miles distant by the track. Some few sheep farms are to be met with in this direction, though the pastoral industry cannot be said to be in a very flourishing condition. It is true that fluke and foot-rot are almost unknown and that wild dogs do not exist in the island, but the scrub must be cleared to a certain extent or there is no grass and it is no easy matter to muster up sheep at shearing. The method which is generally employed in clearing the land for pasture is cutting lanes through the scrub and firing the fallen vegetation in dry weather. In this way the cleared area is extended considerably over the surface in which the scrub has been felled.The greater part of the southern side of the main island is held under pastoral lease by Taylor Brothers, who have recently imported a considerable number of sheep, which it is to be hoped will not disappoint the expectations of their enterprising introducers. The southern country is said to be sandy, and of inferior quality, producing, however, in some localities, fair quantities of salt bush and nutritious shrubs.The journey across the middle of the island from north to south, though only about forty miles in a direct line, is reported to present extraordinary difficulties, not only from the density of the scrub, but from the impassable blind creeks which intersect the ranges. Many attempts to cross the island have been made in vain, but the passage has been successfully accomplished by Mr Giles, the manager of Taylor Brothers Station, a gentleman whose exploring adventures, though over-shadowed by those of his brother, Mr. Ernest Giles, are not unknown to the Australian public.The island is not very prolific of animal life. Emus and dingoes do not exist, kangaroos are practically extinct, and wallabies which lurk in the scrub are by no means numerous. The rabbit has fortunately not yet been introduced, and no attempt has been made to acclimatize the hare. Seals are occasionally met with on the south coast, and gulls, gannets, and cormorants are numerous all along the coastline. Ducks of several species haunt the inland lakes, and pelicans, swans and geese abound on the American River and Pelican Lagoon at certain times. The crow and the black magpie, cockatoos and parrots of several kinds are not scarce, but the Australian magpie, is a rarity.The advantages which the neighbourhood of Kingscote offers as a place of summer resort may be briefly summarized. It is within a few hours’ steam of Adelaide, with which is has also telegraphic communication. The climate is a true insular one, the tempering influence of the surrounding sea prevents the heat of summer from becoming oppressive and even in stormy wet weather it is never really cold. The bay is almost landlocked and offers unusual facilities for bathing and fishing excursions without danger. The scenery of the coast is pretty if not grand and though the back country is not very interesting there are several places at no great distance to which enjoyable pleasure trips might be taken. Visits to Bushy Inlet, where the seabirds breed, to Cygnet River, the further shores of the Bay of Shoals, to Emu Bay, and the American River, may be paid without much trouble or difficulty. Schnapper, snook, and guard fish are said to be plentiful in the bay in good weather, porpoises are occasionally seen, and sharks – though this is no recommendation to a watering place – are reported to abound. The beach slopes gently, and affords good facilities for bathing, but in view of the prevalence of sharks it could not be safely indulged in unless enclosures were provided.Notwithstanding its natural advantages Kingscote at present offers little temptation to visitors. In addition to the utter absence of accommodation, it is extremely difficult – and indeed, often impossible – to hire a saddle horse. Dairy produce is unattainable, for the new settlers have not had time or opportunity to attend to such matters, and the older ones seem to care little about them, but visitors at a watering place will not be content to forego such usual concomitants of civilized life as milk, butter, and eggs, and if Kingscote is to become a place of fashionable resort during the hot months, its inhabitants will have to pay some attention to these things. Kitchen gardening and the cultivation of fruit trees and other matters which are very slightly attended to, and the only vegetable at present obtainable is the potato.The best and indeed the only way to attract the public to any new watering place is to offer them conveniences and advantages superior to those which can be obtained elsewhere. If the Kingstonians are really anxious to secure public patronage they will find it much more efficacious to turn their attention to practical matters than to sigh for a Governor of nautical propensities, who might make the island fashionable by erecting a marine residence there. Of course, the surveyed townships in this neighbourhood are yet in their earliest infancy, and cannot be expected at present to offer any great inducements to the visitor, but with energy and enterprise matters may be made to assume a very different aspect by the time the next hot season begins.From Kingscote to Hog Bay by land is a journey which few people would care to undertake at this time of year. The distance is variously estimated by the islanders whose notions of space are very elastic, at from twenty to forty miles. The latter is probably the more accurate figure, but by sea the distance is about twenty miles, and the Dolphin steams across in a little over two hours.Passing by the bold bluffs that made the entrance to the Eastern Cove, which runs far inland to the Pelican lagoon, and is only separated by a narrow neck of land from Pennington Bay on the south coast, we soon come near to the shores of Dudley and steam into Hog Bay. This little indentation scarcely deserves the name of a bay and affords very scanty shelter from the weather. A little rocky point juts out and makes a scanty break water, behind which boats can land their passengers in safety – unless the wind is from the north or north-east. When this is the case, and the weather is at all rough, Hog Bay is by no means either a convenient or safe landing place. Today, however, the wind, though strong and gusty, is from the west, a boat was sent ashore and the Dolphin is kept under steam for half an hour till it returns.The country around Hog Bay has been settled for some time and is generally reputed to be the best on the island. A good deal of land has been cleared, and the open space looks green and flourishing. There is a veritable township, with stores, boarding houses and even a school. Farther back, the scrub prevails, but the land has been selected right back to the telegraph line which runs through Dudley to Cape Willoughby. The coast land is, however, said to be vastly superior in quality to the inland country and along the American Beach there are some selections which are spoken of in superlative terms.At Hog Bay resides the oldest inhabitant of the island, the veteran Bates, whose experiences date back to the pre-historic times. The record of his life would form an interesting volume and though over eighty years of age, his memory is not so enfeebled that he cannot recall the incidents and adventures of half a century ago. The old man is in very poor circumstances and the charity of the Old Colonists’ Association, which has been invoked on his behalf, could hardly be more befittingly exercised than in smoothing the declining days of the ‘first’ white man who took up his residence in South Australian soil.A few miles from Hog Bay stands, according to the Government maps, the Frenchman’s Rock, on which tradition says the French navigator, Baudin, has left a record of his visit to the island in 1801. Baudin, who commanded the La Geographe, was met by Flinders in the Investigator at Encounter Bay, which received its name in acknowledgement of the recontre. The inscription is perhaps still extant, but several persons who have diligently looked for it, and have met with no success, are sceptical abouts its existence and even go as far as to express doubt that it ever existed.From Hog Bay the run across the Backstairs Passage, though trying to squeamish stomachs, is not otherwise interesting. The Cape Jervis light, Rapid Head, and Aldinga Bay are successively passed, and under steam and canvas the Dolphin rapidly runs up the Gulf and in a few hours is safely berthed at the Port. Her passengers are landed and their trip to Kangaroo Island has passed into the regions of memory.

Incensed by this fairly scathing report on Kangaroo Island, John Christie could hardly wait to put pen to paper to reply –

CORRESPONDENCE“John Christie” referring to an article appearing in the Observer of July 14 entitled “A Few Days on Kangaroo Island”, takes exception to two or three paragraphs in it.He writes that the starting point of the mailboat is from Cape Jervis, and that the mails have never been as late as Tuesday or Wednesday, the latest being Monday night, when they had experienced an unusually rough winter.Also, that the Frenchman’s Rock is not two or three miles from Hog Bay, as stated by our correspondent, but in the bay.Mr. Christie concludes by informing us that the date on the rock is 1883, but if he looks again, we think he will find that he fallen into an error himself, and that it reads 1783.1883, July 20 – Newspaper article in South Australian Register

1884 – Birth – Daughter, Beatrice Alice Christie

A fourth daughter was born at Hog Bay in 1884 named Beatrice Alice Christie.

Throughout all this correspondence with the newspapers, John’s general store succeeded reasonably well for some years, but when the island felt the effect of the depressed economy and his general store business declined, he decided to try his luck in erecting a hotel to provide accommodation to the visitors to the island. At the time, there was no accommodation available and once ashore, visitors either had to bunk down under a tree for the night or beg a bed from one of the island residents.

1885 – Boarding House

So, in 1885, John built a large boarding house of eight rooms at Penneshaw which he deemed suitable for providing accommodation whilst intending to build a further four rooms attached to the building. His progress was reported in the local newspaper –

HOG BAY, August 22The crops are looking well in this district. We have had splendid rains during the past week, and should the season continue as promising, a good return may be looked for.Mr. John Christie is now building a large boarding house in Penneshaw township.1885, August 29 – Newspaper Article in South Australian Weekly Chronicle

However, the authorities refused to issue him with a hotel license on the grounds that the accommodation he was offering would not meet the needs of those who chose to patronise the place, and suggested he improve his building to meet this objection.

ADELAIDE LICENSING BENCHQUARTERLY MEETING, Adelaide, September 14Applications for Publicans’ New Houses – John Christie, Penneshaw Hotel, Penneshaw, Kangaroo Island.Mr. H.E. Downer for the applicant. Mr. W.R. Wigley for Inspector who opposed the application because the applicant’s house was not sufficiently large to meet the demands of the residents and visitors.Mr. Downer said that Mr. Christie wished to have a license for a hotel situated in Hog By, where there was an utter absence of accommodation. There was no hotel accommodation on the island except at Queenscliffe, which by the land from Hog Bay was 40 miles distant, the nearest place on the land side being Finnis Vale. The house proposed for the hotel comprised eight rooms, but Mr. Christie intended to add four other rooms to the house if a license were granted.Persons visiting the island were entirely dependant upon the charity of the residents to get a suitable bed and meal. Hog Bay, with a population of about thirty, had been settled for several years, and the residents were in favour of a hotel for the township.Mr. Wigley intimated that the house as at present would not meet the requirements of those who chose to patronise the place, but if it were improved or a better one erected the Inspector would not oppose the application.Application refused, because the plans did not show the accommodation that was considered necessary by the Bench. Liberty given to apply again with better plans at the next quarterly meeting.1886, September 15 – Newspaper Article in South Australian Register

1887 – Return to the Mainland

John, frustrated at the barriers thrown in his way by the licensing conditions, chose to uproot his family from Hog Bay and return to the mainland in 1887, but not before another daughter, Bertha Christie was born there in 1886.

John was clearly well respected and well liked in his community at Hog Bay as seen in the following articles –

COUNTRY CORRESPONDENCEHOG BAY, January 27On Monday, January 24, a large number of people assembled on the beach at Hog Bay to bid farewell to Mr. John Christie and family, who were going to Adelaide by the James Comrie.Mr. Christie came to Kangaroo Island about nine years ago when he kept a public store at Hog Bay until about twelve months since. Mr. Christie was, however, previously known to Kangaroo Island, for during the last twenty-three years he carried the mails across from Cape Jervis to Hog Bay. He was a resident well-liked and respected.1887 – February 2 – Newspaper Article in South Australian Register

HOG BAYOn Monday, January 24, a large number of people assembled on the beach here to wish goodbye to Mr. John Christie, who was about to leave the district. Not much time was available for speech making, but after a few words of farewell, Mr. Christie sailed amidst the cheers of those present.Mr. Christie’s connection with Kangaroo Island dates from about 23 years back, when he and his father successfully ran the mail across Backstairs Passage for a number of years.At last, he tendered, unsuccessfully, for the transport of the mail, and decided to start a general store at Hog Bay. Mr. Christie did a good business for several years, but the recent depressed state of trade induced him to try some new line of business.Accordingly, he built a hotel here, but failed to procure a license. Mr. Christie then endeavoured to sell out, but was unsuccessful, and on a second application he was granted a license on condition that more accommodation was afforded by the hotel.Mr. Christie not being in a position to make the necessary additions, felt himself compelled to leave the district.His absence will be felt, as he always did his best to enhance the interest of Hog Bay. He takes with him the best wishes of the majority of the islanders.1887 – February 5 – Newspaper Article in South Australian Register

1889-1891

Another daughter, Violet May Christie, was born at North Brighton in 1889, but died at 21 months old at Edithburgh in 1890.

Violet was followed by Sarah and John’s last child and only son, born in 1891, named Lendsley Harold Christie.

1895 – Death – Sarah Jane Warren

Sarah Jane Christie, nee Warren, died at her home in Edithburgh on January 11, 1895. She died from Graves’ Disease which is an autoimmune disease that causes the thyroid to overproduce and over-secrete thyroid hormones. This results in hyperthyroidism.

1921 – Death – John Christie

John Christie continued to live at Edithburgh after the death of his wife until his death in 1921.